Jamie Bragg

And Still the Dust Clings

4 Dec 2025 – 7 Feb 2026

Sun is an ever-present constant in Bragg’s invocation of the pastoral; rays transposed onto the scenery through shadows cast by olive branches and figures shielding their eyes. Its beams are searching, bleaching the canvas into wearied submission. The florid sweetness of native poppies and long grass turn sickly as they endure her heat.

This over exposure gestures to the photographic form from which the subject matter originates – flash photography, gestated in darkrooms and overblown into lightness. Despite its seduction, this painterly process is one of violent metamorphoses, from photographic film to object; a ritual confronted by Bragg’s use of whitewashing and fluorescence. His paintings are situated amid the volatile lifespan of the photo, the momentary agency of the image-taker subverted by the mode of rendering. Portraits blur to mugshots, landscapes into eulogies. And yet, these mise en abymes are acts of sacramental devotion, a bucolic pastiche of found images that feel at once strange and familiar in their composition.

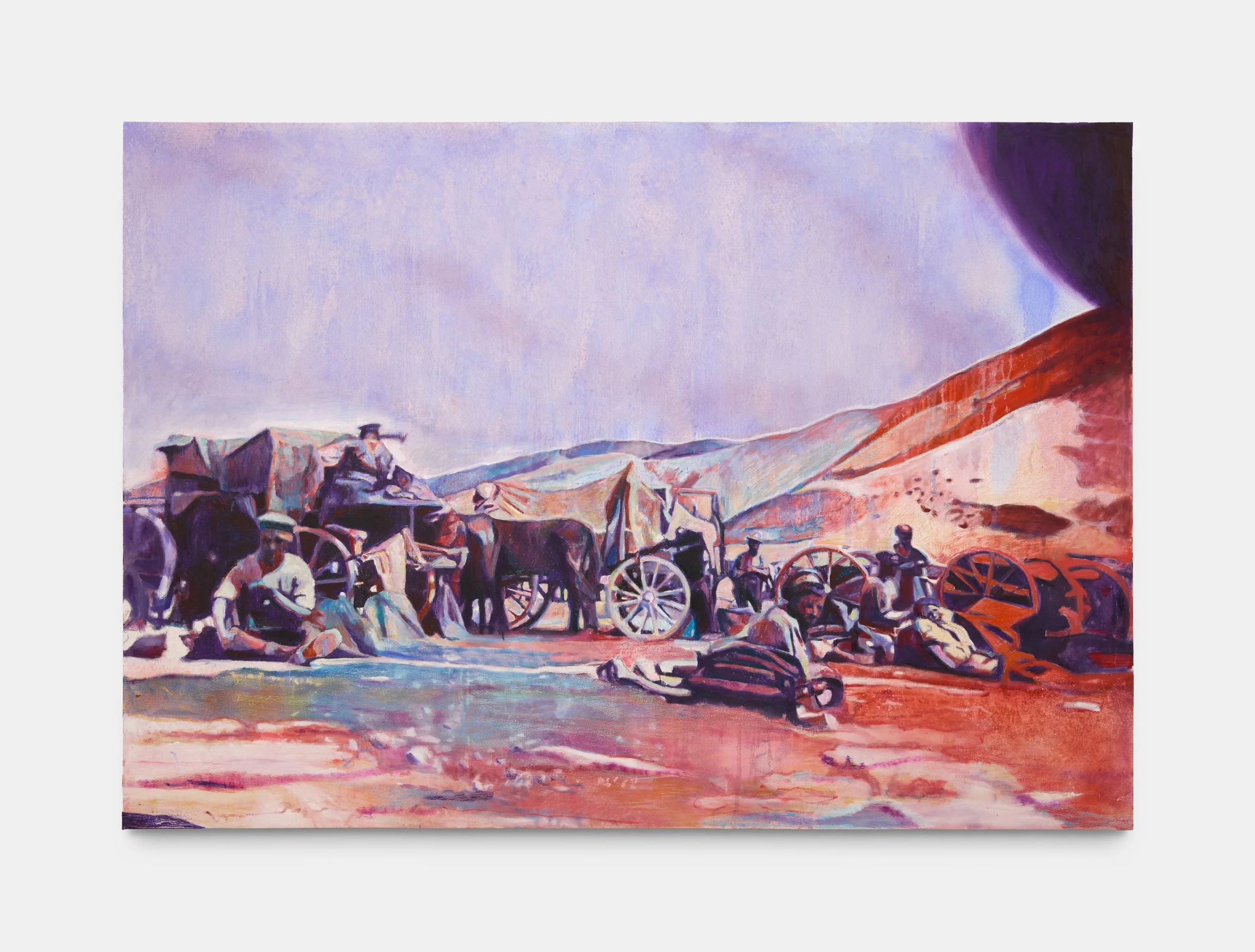

Bragg’s facture intends to slow the act of looking, wrestling complicity through tokens of a discontented past. A wad of photos from his great-grandfather, Willis, serve as source material, taken in subterfuge during his service in North Africa and the Levant in WW1. Bragg both reveres and admonishes these depictions in his work. In paint, entangled limbs come in to focus, clasped hands and gripping arms betray a rich tenderness (Carts ‘n’ ‘orses, Salonica 1916, 2025). Touch is exchanged freely, a currency of kinship in abundant disposal; men become cowboys astride ambling horses; soldiers slumped against one other, sometimes eerily languid in their rest. His pastel colours lend themselves to a nostalgic romance of military life, in which shade is a welcome reprieve from the heat and trappings of social decorum. In Dozing in the Dunes, Egypt 1916, 2025 men yield to this primality with boyish abandon. But these muted tones intimate a deeper turbulence. Slivers of red bleed into bruised yellows and purples, brewed angry by time; seemingly arcadian vignettes are marred by the long shadow of colonialism.

Paint is layered, as if itself the craggy topography of the land, built up and scratched down, scumbled and then pasted thick, evocative of the Levant’s roily and evolving history. The sky is a spray of cloud, cumulus grown heavy with rain. On the ground, spray takes a different form, tarnishing the earthen floor with a generous spattering of rust. Paintings are flanked by hard-faced men, a foreign presence in these storybook landscapes (Foster and George). Their undulating glare dares you to look beyond to the rolling hills and convivial scenes of picnicking soldiers, their stances foreboding some ill fate, hands slung on hips, restlessly furtive. Everywhere, swarthy gazes betray knowing. Absent looks bore outward from a snapshot in time.

Bragg toys with the imaginings of the cameraman, who’s written form narrates these scenes. Notes scribbled on the back of photographs suggest the gaiety of one writing home from their travels: ‘My pal Dixon with my chum the Donk!’. But, behind the central figures lurks a land of contested ownership, hills that now lie either populated or destroyed. Animals are characters at play in Bragg’s work, as much a part of the scenery as the trees and the hills. They too are a phantasmic presence, the erasure of which transcendentally haunts these compositions. The palette glows with remnants of a discomfited legacy, shadowed purple and scuffed down (Donkey Buried Under its Load, 2025). Time’s linearity is, itself, fractured by this provocation. Rarely are we privy to the respite of R&R. That is, bar Full Dress Uniform, Barnes 1914, 2025. Here, the dressings of homeliness are cast against a uniformed figure, the disjunct of strange and familiar in domestic confrontation.

Bragg’s work vibrates uncomfortably between this very proximity of violence and tenderness, tugging threads of complicity from the weft of the canvas. His practice is one of introspection, seeking to unravel a trail of generational culpability through social artefacts, warding against the passivity of unchallenged memory. Every painterly illusion is subject to his unflinching gaze, just as no creatures roam free from the captor’s lens.

Text by Lucy Phillips

Jamie Bragg (b. 2001, Watford, UK) lives and works in London. Bragg’s paintings probe the uneasy space where private memory collides with collective history. He works from an ever-evolving archive of found and inherited photographs, most recently, images taken by his great-grandfather during his military service in North Africa and the Levant.

Bragg translates these artefacts into quiet, pastel compositions that oscillate between delicate intimacy and unease. For Bragg, these works function as both gestures of care and acts of confrontation, situating tenderness and violence in fragile proximity. Bragg’s process begins with digital collage. Photographic sources are fused and re-formed into new, dislocated compositions that strip the images of their original context. Slowly, these are then rendered with a focus on tactility: pigment is layered, paint sprayed, scumbled, scratched, and wiped back to create an enticing surface. The act of looking is intentionally slowed. Through this seductive handling of paint and colour, he amplifies the tension between the compositions’ formal beauty and the disturbing legacies that they hold.

Within his canvases, Bragg reframes family photographs, not as neutral fragments of the past, but as charged sites in which grief, nostalgia, intimacy, and complicity converge and endure.

Bragg graduated from the Ruskin School of Art, University of Oxford, in 2024, where he was the winner of the Mansfield-Ruddock Prize, selected by Sir Nicholas Serota and Joy Labinjo.

Bragg has exhibited at Gathering, Ibiza (2025), Modern Art Oxford (2024), and The Dolphin Gallery, Oxford (2024). Bragg was nominated for LUX Next Gen Masters: The Bicester Village × LUX Magazine (2024) and The Platform Graduate Award, Oxford, UK (2024) and was the winner of The Oxford Review of Books Art Prize Spring Edition, Oxford, UK (2024).